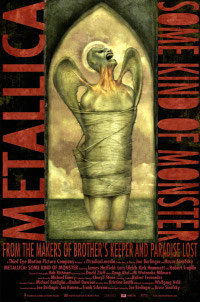

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster

The best part of Metallica: Some Kind of Monster is its reputed backstory. Commissioned by Metallica’s record label as a promotional film about the making of the metal band’s new album, it instead documented the group’s near-implosion. The middle-aged rockers bought the film from the label mid-shooting and allowed it to be finished and released with (apparently) little interference.

The best part of Metallica: Some Kind of Monster is its reputed backstory. Commissioned by Metallica’s record label as a promotional film about the making of the metal band’s new album, it instead documented the group’s near-implosion. The middle-aged rockers bought the film from the label mid-shooting and allowed it to be finished and released with (apparently) little interference.

The finished product represents, first and foremost, a statement by Metallica of its incorruptible integrity, as well as its utter lack of vanity. The band is so noble that it not only agrees to but encourages a movie that shows the members’ fights, their insecurities, and their tendency to behave like spoiled, bratty kids.

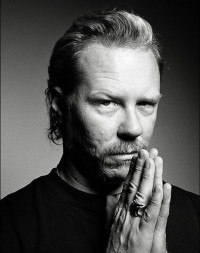

Yet as engaging as the film is, it’s still strangely amiss. It’s lean but feels too long; it’s probing through the camera’s omnipresence but too gentle and polite; and it’s revealing without ever getting to the heart of the band or its leaders. The biggest hole is that its most compelling character – singer, guitarist, songwriter, and generally tortured soul James Hetfield – is missing for maybe half the movie and is also the least-open member of the band.

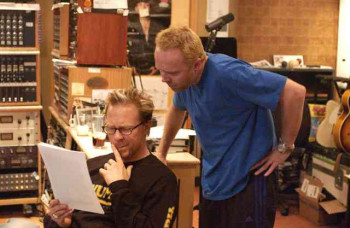

This ultimately fatal flaw isn’t easy to find, though. Filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky (Brother’s Keeper) populate Some Kind of Monster with dozens of great candid moments, from multimillionaire rock star Lars Ulrich agonizing while waiting for his father’s blunt criticisms (and unconsciously aping his every gesture) to the poignant but shockingly long-held hurt expressed by former Metallica guitarist Dave Mustaine to the only way anybody can get a rise out of que sera, sera guitarist Kirk Hammett – by suggesting the elimination of the guitar solo on the St. Anger record. Most endearing of all is watching new bassist Robert Trujillo – a fairly successful musician in Suicidal Tendencies and most recently with Ozzy Osbourne – unable to control his glee at being asked to join the band.

The movie is built on a premise of full access, and it certainly gives the impression that you’re seeing something rich. But it feels incomplete, and in retrospect you see that it’s because the film is all skillfully assembled surface detail. The reality is that you don’t know Metallica much better – as artists or people – from watching Some Kind of Monster than you would from being a casual fan over the years. A friend and fellow movie critic described the movie as the best episode of Behind the Music ever, and at first I disagreed; now I recognize that he was right, although I read something derogatory into what he meant as a compliment.

Viewers would be smart to approach the movie with skepticism. To start, Berlinger and Sinofsky are an odd choice to make an extended infomercial for Metallica. The pair made the acquaintance of the band while putting together Paradise Lost, to which the group donated songs, so there was a previous relationship. But why hire serious documentarians for such a crass project?

Unless … somebody anticipated what was to come.

As the movie begins in 2001, longtime bassist Jason Newsted has quit Metallica, and while his absence really shouldn’t matter – he was never given much to do, and he could barely be heard on-record – it prompts a crisis of faith. Hetfield is squabbling seriously with smoldering drummer/songwriter Ulrich, and feckless guitar wanker extraordinaire Hammett – the Derek “lukewarm water” Smalls of Metallica – is left to twirl his greasy hair. The band has enlisted $40,000-a-month counselor Phil Towle to help the members work through their differences and facilitate the writing and recording of a new album.

Assuming the cameras started rolling roughly when the movie begins, only a recording-industry moron would have let filming commence, let alone drag on through ever-escalating drama. Why expose such a valuable label property at three-quarters strength, with its bickering and its new-age consultant and a recording process that starts with nothing written? Unless … .

Things quickly turn even sourer than they started. Hetfield – the soul of the band, the only member with a dispositional menace to match the group’s music – bolts for rehab. He doesn’t return for nearly a year.

The stated reason for Hetfield’s absence is alcoholism and other substance-abuse problems, but based on what’s in the movie, it looks as if he’s simply fed up and wants to get the hell away from Ulrich. And this is where Some Kind of Monster falls utterly flat: It presents little evidence of Hetfield’s drinking problem, and – even worse – he never addresses it in front of the camera once he returns. It feels almost like a ruse.

The stated reason for Hetfield’s absence is alcoholism and other substance-abuse problems, but based on what’s in the movie, it looks as if he’s simply fed up and wants to get the hell away from Ulrich. And this is where Some Kind of Monster falls utterly flat: It presents little evidence of Hetfield’s drinking problem, and – even worse – he never addresses it in front of the camera once he returns. It feels almost like a ruse.

The whole enterprise seems contrived, an attempt to scratch up the image of a band that had probably become too polished over the years. Starting with 1991’s Metallica and running through the surprisingly strong S & M – in which a symphony orchestra showcased the compositional assets of the band’s older material – the metalheads found themselves solidly in the mainstream, and all too comfortable.

What you see in Some Kind of Monster is nothing less and (sadly) nothing more than a band engaging in one of its periodic bouts of self-evaluation. The group’s career is easily broken down into 10-year chunks – the thrash years (1981 to 1990) and the Bob “pop” Rock period (1991 to 2000). The Metallica that emerges from Some Kind of Monster is leaner and meaner than what came before, but getting there is quite the journey.

For the first time, Metallica came into the studio without anything written. The jamming and lyric brainstorming are indeed painful to watch and hear, although it’s instructive to see songs hammered out through so much shit, rarely if ever birthed fully formed from the ether of inspiration. Some Kind of Monster is best at showing the dynamics of a dysfunctional group of human beings in the creative process, and it’s beautiful to see how songs come together and how they relate to what the band has gone through.

But it’s not anything more than a superior music documentary. The human elements are rudimentary at best: See Lars get drunk as he sells his collection of modern art. See Kirk on his posh estate. See wives and kids come and go, but never stay very long. Don’t see James. And when you do see him, don’t look at him, because he doesn’t want you to and will kick your ass.

The audience is held at a curious distance. Mustaine – who formed Megadeth after getting kicked out of Metallica – is emotionally naked for his brief appearance, and it highlights how guarded the band members are. Yes, they fight, and yes, Hetfield abandons them,

but it all just sits there. The filmmakers don’t seem interested in delving deeper, into Hetfield’s demons or the apparently-always-prickly relationship between him and Ulrich.

Some Kind of Monster is, ultimately, very much like the band it documents: generous to an extreme, but very selectively.

Metallica has always had a certain duality about it. The group gives its fans a ton – with relatively long albums and three-hour shows – yet it’s never been particularly prolific. Between 1986’s Master of Puppets (the group’s commercial and artistic breakthrough) and Some Kind of Monster, Metallica released only five albums of new material. That’s nearly four years between records, on average.

And in 2000, the band began a famous battle with the file-sharing service Napster, arguing correctly if shortsightedly that people were stealing Metallica’s music. What the group failed to recognize was that downloading music for free was, among other things, a clear and obvious act of rebellion against a record industry that gouged consumers to offset massive amounts of up-front money given to performers with at-best-arguable long-term commercial appeal. (Yes, I’m talking about you, Mariah Carey.) Metallica attacked a symptom when it should have used its considerable muscle to target the disease, and in the process showed seriously bad judgment.

The Napster debacle gets glossed over in Some Kind of Monster, just like Hetfield’s problems and recovery. Yes, by the time the movie starts, it’s old news, but it was a defining low point for Metallica in general and Ulrich in particular. Berlinger and Sinofsky should have confronted him about it and asked the tough questions, just as they should have forced Hetfield to talk about his alcoholism. But that’s not their style; they want their cameras to be all-seeing wallpaper, not inquisitors.

As a result, even though Some Kind of Monster is without parallel as a portrait of a band desperately needing and trying to re-invent itself, it is sorely lacking as a human story.