Interpretation Trumps Inspiration

Rather than merely join the chorus of those who dismissed Brian De Palma’s The Black Dahlia, and rather than cast a dissent from the general critical favor accorded The Illusionist, I’ll respond to critics I enjoy and respect whose perspectives on these movies differ significantly from mine.

Rather than merely join the chorus of those who dismissed Brian De Palma’s The Black Dahlia, and rather than cast a dissent from the general critical favor accorded The Illusionist, I’ll respond to critics I enjoy and respect whose perspectives on these movies differ significantly from mine.

Because I do have a memory – not a very good one, but a memory nonetheless – I can save myself some work by providing Rupert Murray – the filmmaker behind Unknown White Male – with a few lessons I’ve learned from other movies and simply link to previous essays.

Because I do have a memory – not a very good one, but a memory nonetheless – I can save myself some work by providing Rupert Murray – the filmmaker behind Unknown White Male – with a few lessons I’ve learned from other movies and simply link to previous essays. Marnie is narratively and technically artless – literal and obvious and shrill and nearly naked in its themes and concerns, a story clumsily built around Freudian repression. Yet Marnie is not the travesty many people think.

Marnie is narratively and technically artless – literal and obvious and shrill and nearly naked in its themes and concerns, a story clumsily built around Freudian repression. Yet Marnie is not the travesty many people think. The unfathomably fashionable torture film has spun off a welcome girl-power subgenre, in which determined, attractive young females facilitate the agonizing dispatches of men who have committed atrocities against youth. But two early entries – Hard Candy and Lady Vengeance – are misguided.

The unfathomably fashionable torture film has spun off a welcome girl-power subgenre, in which determined, attractive young females facilitate the agonizing dispatches of men who have committed atrocities against youth. But two early entries – Hard Candy and Lady Vengeance – are misguided. In Inside Man, director Spike Lee and screenwriter Russell Gerwitz announce early that nothing too traumatic will befall any of the characters, and then they keep that promise; they implicitly give the audience permission to enjoy the film.

In Inside Man, director Spike Lee and screenwriter Russell Gerwitz announce early that nothing too traumatic will befall any of the characters, and then they keep that promise; they implicitly give the audience permission to enjoy the film. The disappointment of Christopher Nolan’s enormously entertaining – and slyly provocative – The Prestige comes in its closing minutes, when it adds a fourth act to its illusion: the final reveal. As any magician will tell you – as the movie itself reminds the audience – knowledge of the secret robs the trick of its power and allure.

The disappointment of Christopher Nolan’s enormously entertaining – and slyly provocative – The Prestige comes in its closing minutes, when it adds a fourth act to its illusion: the final reveal. As any magician will tell you – as the movie itself reminds the audience – knowledge of the secret robs the trick of its power and allure. The suspension of disbelief, to borrow a hackneyed maxim, is a privilege, not a right; you need to earn it. And last year’s holiday hit The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe doesn’t.

The suspension of disbelief, to borrow a hackneyed maxim, is a privilege, not a right; you need to earn it. And last year’s holiday hit The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe doesn’t. The temptation when writing about Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story is to try something really clever.

The temptation when writing about Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story is to try something really clever. The true subject of Albert Brooks’ Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World is the fact that most people don’t find Albert Brooks funny. That sounds sour, and it sells the movie short, but it’s fundamentally true. Plus: V for Vendetta.

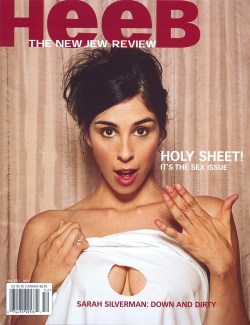

The true subject of Albert Brooks’ Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World is the fact that most people don’t find Albert Brooks funny. That sounds sour, and it sells the movie short, but it’s fundamentally true. Plus: V for Vendetta. Sarah Silverman is no Snakes on a Plane, but the slapdash movie bearing her name suffers from the same problem: overexposure.

Sarah Silverman is no Snakes on a Plane, but the slapdash movie bearing her name suffers from the same problem: overexposure.